The Last Baby: Why the Global Fertility Crisis is the Greatest Threat Facing Humanity Today

A Deep Dive on a Looming Geopolitical Crisis

The sounds of spontaneous laughter and play are fading into memory in the streets of nations across the globe. Playgrounds empty, primary school enrollment numbers dwindle, and populaces gray and wrinkle in a creeping silent crisis.

Go for a stroll through any German village, Spanish town, or Japanese hamlet and you won’t be able to ignore the abundant signs of age. The paths where boisterous youths once ran their routes to primary school are now traversed by middle aged, Strava-obsessed joggers. Cashier tills of shops, once manned by bands of teenagers, are now operated by graying seniors and queues outside of arcades have shifted to the fronts of pharmacies. Through no fault of the elderly individuals, these communities have naturally succumbed to a less lively, less optimistic atmosphere as a level of hopelessness takes hold in the wake of abandonment and dereliction.

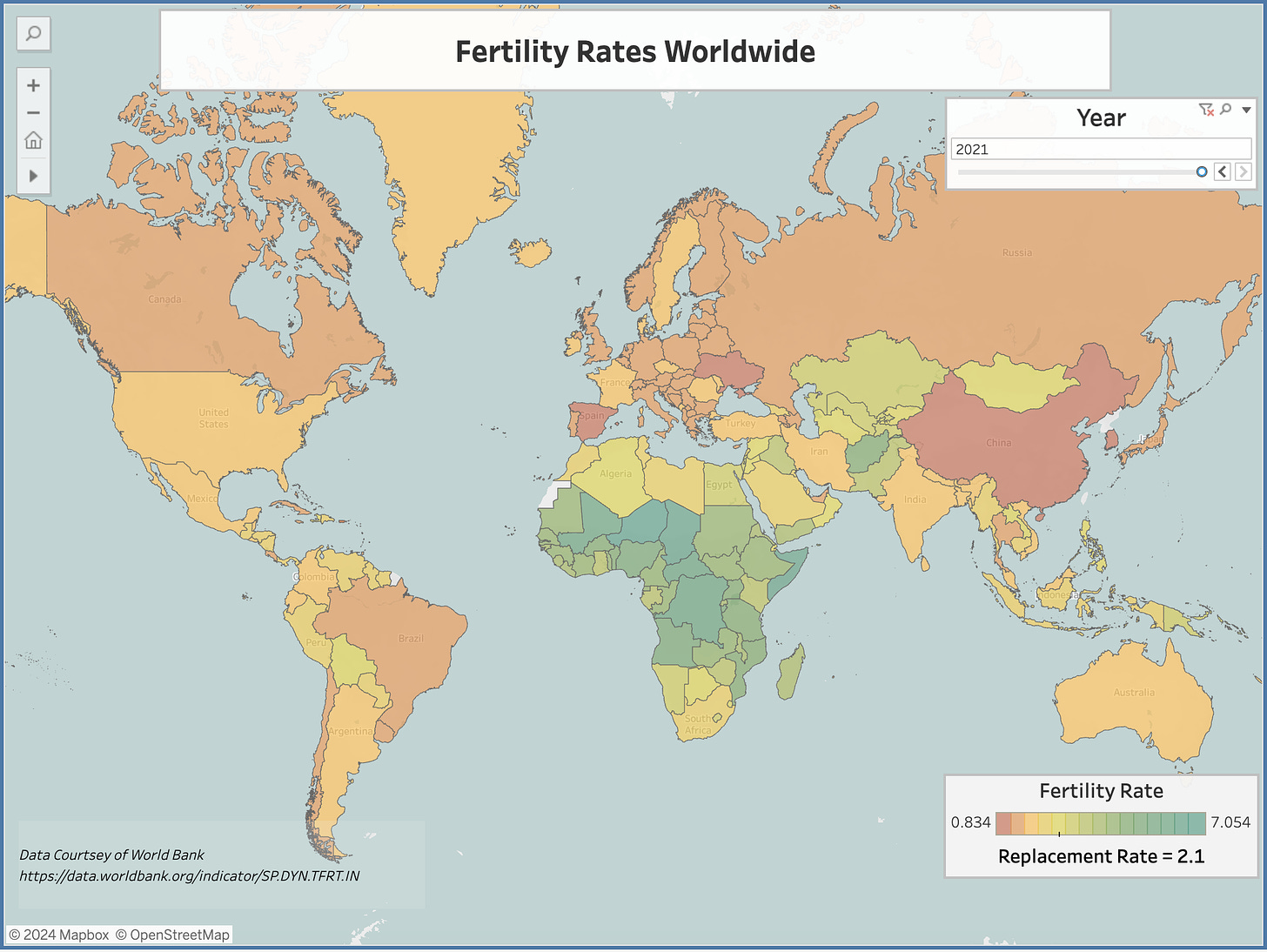

Unbeknownst to the members of these fading locales, their situation is indicative of a much larger global phenomenon, with over 100 nations falling below the replacement rate fertility of 2.1 births per woman. The implications of this impending crisis span far beyond politics and economics, to the very fate of humanity itself.

In the 70s, 80s and 90s overpopulation was all the buzz. Authors, demographers and scientists instigated a worldwide panic after interpreting the seemingly exponential growth in the human population as an existential threat. Books advocating for mass sterilization became bestsellers, international organizations and governments rallied against excess birth, and billions of lives were altered by the paranoia of the overpopulation cult.

Inspired by these alarmist predictions many radical laws came into fruition, limiting individual human freedoms in ways never conceived of before. Most notably among these was China’s One Child Policy in 1980, which prevented an estimated 400 million births. China was not alone in their use of State-sponsored family planning however, as leaders in South Korea, Vietnam and Singapore passed legislation to stifle large families and promote birth restrictions. In a particularly horrific instance, the Fujimori Government of Peru conducted ethnic cleansing under the guise of progressive and enlightened overpopulation control program. Utilizing funds and resources from USAID and the UN’s Population Fund, Peru forcibly sterilized hundreds of thousands of indigenous Andean women.

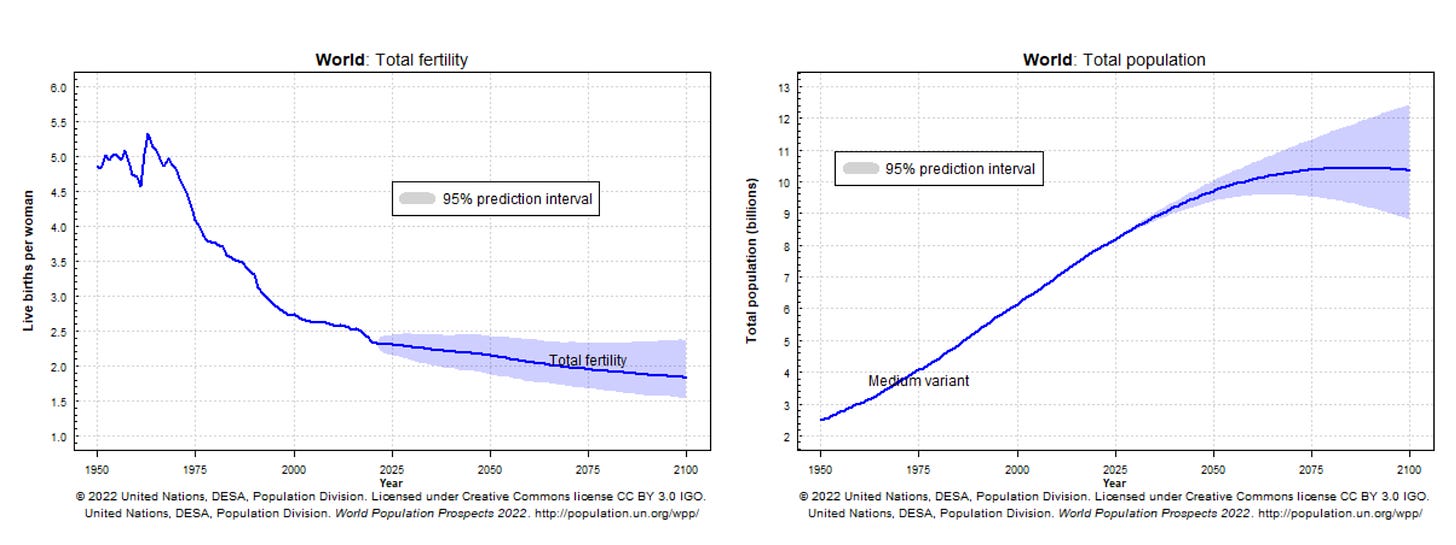

In the last twenty years, all of the anti-birthing programs have been abandoned as a new consensus is realized: the world is not heading towards ‘overpopulation’, rather, it is rapidly approaching the opposite. The world population is projected to peak and taper off in the next fifty years at around 10.5 billion people. While that number may seem disconcerting in the face of climate instability and war, the majority of this growth will be sustainable. The greatest population change will occur in Africa, a massive and relatively underpopulated continent with 65% of the world’s arable land. In addition, world agriculture already produces enough food to feed 10 billion people which, if distributed equitably, will be sufficient to feed the globe’s peak populace.

The countries which enforced anti-birthing policies experienced the greatest declines in fertility, however, these programs were ultimately unnecessary as the fertility rates of dozens of nations have plummeted without government interventions. While most associate declining fertility with East Asia and Southern Europe, serious drops have occurred in every continent, with sub-replacement fertility rates now occurring in India, Brazil, and Iran. The reasons for the fall in fertility are as complex and multifactorial as life itself. Urbanization, contraceptive technology, shifting gender roles, cultural changes, irreligiosity, and economic inequality are some of the main factors driving the worldwide trend. But declines in fertility are also linked to concerns over climate change, plummeting sperm counts, and even the 2008 financial crisis.

Explore our Fertility Rate Dashboard by Year & Country Below:

The Land of the Setting Sun

Declining fertility rates pose serious existential risks to societal structures and to modern governments as we know them today. To glimpse into the grim future awaiting the world, look no further than modern Japan, where adult diapers are sold in greater numbers than those for infants.

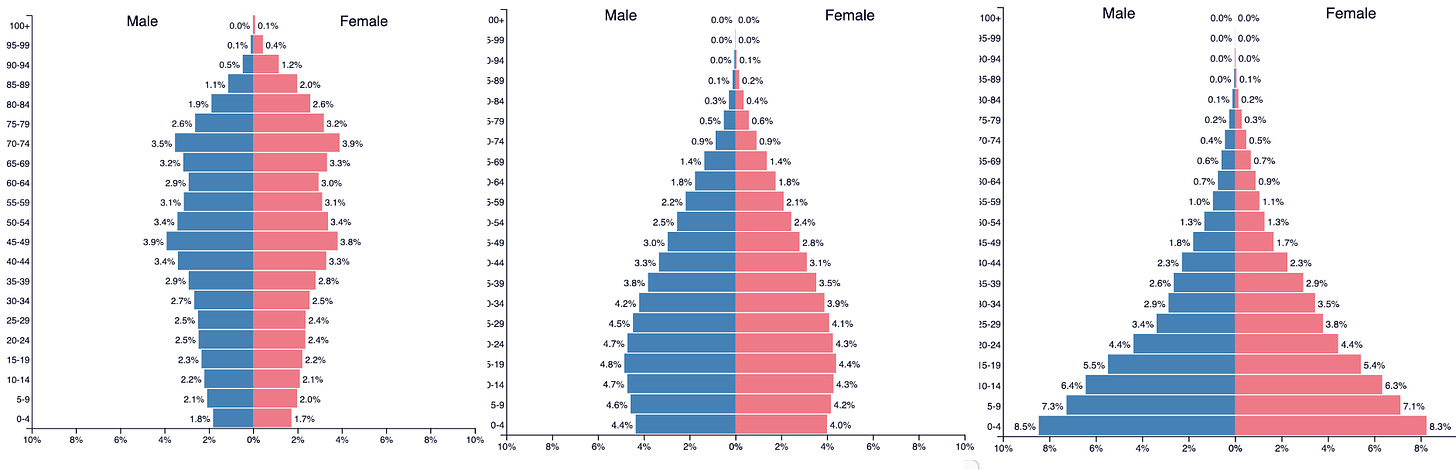

Emerging from the devastation of World War 2, Japan underwent a miraculous turnaround. Industry rebounded, the population recovered, and trillions in wealth were accumulated. The standard of living rose alongside the economy, and Japan became one of the best nations on Earth to reside, visit, and invest in. However, social planners and policy-makers ignored the writing on the wall. Since 1960, Japan has consistently had fertility rates below replacement rate alongside nearly zero immigration. The situation has caught up with the East Asian giant as the population pyramid has flipped on its head, with older generations now making up the majority of the populace.

Japan’s economy now faces a dual crisis of consumption and production. Consumption of goods erodes each year as demand dissipates in the absence of a large youth population. In order to stimulate or sustain growth, the country has to export the bulk of its goods, which Japan does at an ever-increasing pace. However, without sufficient labor to replace their aging workforce, labor shortages occur and goods become more expensive to export.

To save their export competitiveness, Japanese companies have automated massive parts of the production systems. While this automation staves off the effects of a disappearing workforce, industrial robots can’t stimulate domestic growth through the money-multiplier effect as, unlike workers, they receive no wages to spend. In addition, robots cannot create new innovations, which are critical to Japan’s competitiveness in tech.

In lieu of domestic consumption of goods, the majority of economic activity shifts to services, especially healthcare. This shift poses two problems for Japan. First, services, unlike manufacturing roles, are much more difficult to automate, although unsettling attempts are being made to robotize nursing. The second issue is one of private vs. public spending. For nations such as Japan with enshrined public healthcare schemes, the majority of this spending comes from the taxpayer or through debt-financing, not directly from consumers. This creates ever-burgeoning public spending commitments and has contributed to Japan undertaking the greatest debt ratio of any nation on Earth.

To read more about Japan’s Mega-Debt check out our article here

Japan’s trajectory is unsustainable, eventually, something has to give. Without a major cultural shift or mass immigration, which has its own host of controversies, Japan is doomed. At first, measures will be proposed to push back the retirement age, cut back social spending, and accelerate debt borrowing. However, any policies cutting elder-benefits will be extremely difficult to sell to an old public which holds the vast majority of the vote.

A possible scenario thus emerges in which over time the economy grinds to a halt, social welfare systems break down, the nation defaults on its debts, and the currency nosedives. The young generations remaining will be left with few options. Many will either flee in search of opportunity or will be courted by increasingly radical political movements. In the wake of a failure of democratic governance, it is extremely likely that authoritarianism will reemerge. The prospects for a capitalist social democracy surviving such a crisis are very very low.

What Are Governments Doing:

Japan is one of the first nations to experience the windfalls of the fertility crisis, but is certainly not the last. Governments around the world have been attempting to revert the trends for decades. Some have been marginally successful, others have failed miserably.

Deemed an emergency situation by Japan and South Korea, both have committed hundreds of billions in the last fifteen years to childcare vouchers, direct grants, and parental leave policies. Unfortunately, these policies have been fruitless, as the fertility rate has continued to fall in Japan and has plummeted to a world record low of 0.78 in South Korea. Experts predict a halving of the South Korean population in the next fifty years.

China shares in South Korea's woes, and is on course for mass depopulation as well. The ‘World’s Factory’ is severely hindered by both an extreme gender imbalance and a fertility crisis accelerated by their disastrous One Child Policy, which wasn’t eased until 2016. This trend should be of deep concern for the Communist Party, which has relied on Chinese manufacturing labor to build the nation’s incredible economic strength in the last thirty years. However, the central government has been slow to act. So far there has only been nationwide action through menial awareness campaigns against abortion and some subsidies for IVF for married couples. The government still restricts Chinese couples to a three child policy.

Chinese lawmakers, constrained by bureaucracy and the Party’s past stances, will not be able to reverse the fertility declines with these limited measures alone. The same pressures constraining Japan’s growth are certain to severely affect China in the coming decades, and their newfound geopolitical might will be difficult to sustain in the face of prolonged stagnation. Without significant societal reform and major cultural change, the predicted ‘Chinese Century’, will likely never come to fruition.

The Czech Miracle: Fluke or A Light at the End of the Tunnel?

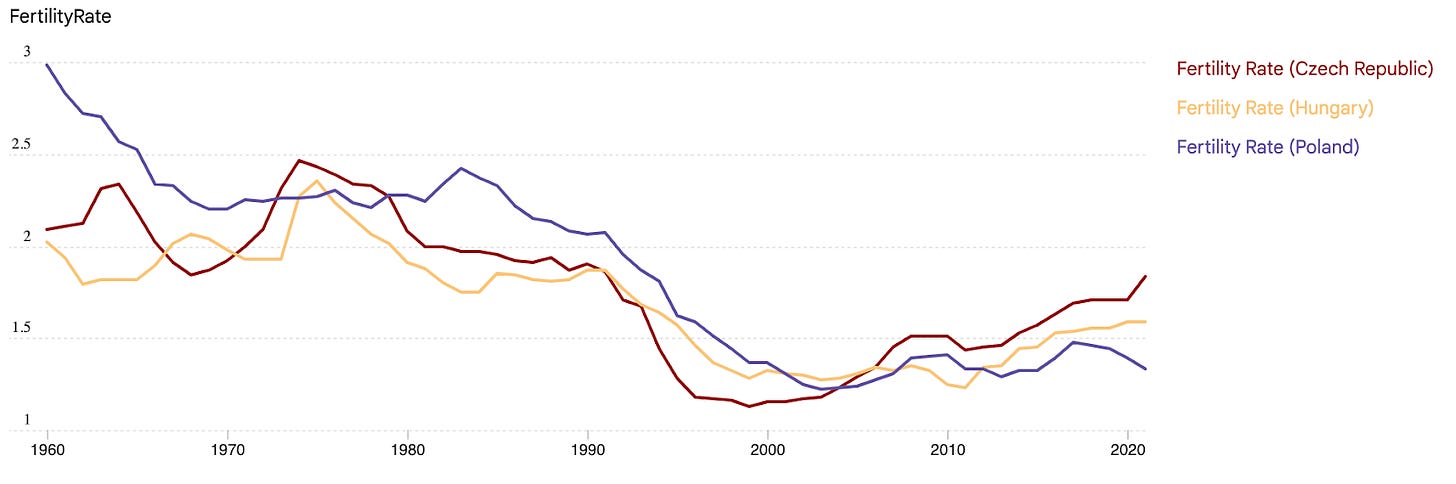

Leaders in Central Europe have gone to great lengths to reverse the demographic trends of their nations, with some success. In the late 1990s, the fertility situation in post-communist Central Europe was dire, opportunities were limited and fertility rates bottomed out, barely above 1. Decades later, the governments of Hungary, Poland, and the Czech Republic spend up to 5% of GDP on family policy alone, which is relatively a larger commitment than the USA has towards its military budget.

With help from the State, fertility has rebounded in the Czech Republic, the highest fertility rate in Europe, rising from 1.1 in 1999 to 1.83 in 2021. According to natal policy experts, the rise was attributable to generous parental allowances, major investments into early childcare, three year maternity leaves and housing assistance. A crucial complement to these policies has been the sustained low unemployment rates and cultural attitudes which emphasize the importance of children to society. This change of fertility was also achieved without a large influx of immigrants, who only make up 6% of the Czech population.

Sustainable Fertility

Why has the Czech Republic succeeded where its neighbors Hungary and Poland, as well as the aforementioned South Korea, have failed? Sociologists attribute this to several components, chief among them are views towards family life, unemployment rate, and housing affordability.

In a strange irony, traditional family roles may not hold the key to higher fertility. Hungary’s Victor Orban, in accordance with his nationalist agenda, has advocated for a return of women to the home as a potential cure to the fertility crisis. However, evidence indicates that female labor participation and fertility are not negatively correlated. In fact, many European nations with the highest female labor participation, such as Sweden, Norway, Denmark, and France have higher fertility rates than other European counterparts with far lower female workplace participation.

The European nations with the highest fertility rates have an ideal combination of familism (desire to have families), more relaxed norms of family structures, and significant government support to facilitate a balance between work and home life. This work-life balance appears to be an essential ingredient for rebounding fertility. In the United States, couples listed the top two reasons for not having children as financial stress and an uneven work/life balance. In the US and in many other Western countries, there hasn't been a decrease in the desire to have children; rather, there has been an increase in concerns about affording their upbringing and dedicating the necessary time to raise them.

“each instrument of the family policy package (paid leave, childcare services and financial transfers) has a positive influence on average, suggesting that the combination of these forms of support for working parents during their children’s early years is likely to facilitate parents’ choice to have children”

Despite having much better fertility prospects than most nations, the egalitarian European States haven’t completely solved the puzzle yet. Family-friendly policies may raise or stabilize slumping rates, but overall fertility rates still trend below replacement in all of Europe.

Looking Forwards

The fertility crisis, festering, lumbering, and methodical, is a far cry from the sexy and dramatic exit many have envisioned our species taking. Distant from a apocalyptic exchange of nuclear weaponry or a super-pandemic to rule them all, this meandering and self-imposed crisis of choice slowly poisons us. The tribulations of modern life, market capitalism, and years of inactive or antagonist government policies have compounded, pushing our societies down a catastrophic path.

On a micro-level, our infertile future presents grim outlooks to the communities we call home. Slowly declining and fading, the joy and wonder of children will be supplanted by the cynicism and stasis of age. The macro-outlook, however, is far more concerning. Our future is one in which social security networks, which have provided immense wellbeing to our populaces, become unviable and obsolete as GDP’s pale in comparison to elder-care spending. In the wake of failed promises and unwinding safety-nets, democracies will become less and less compelling as radical social upheavals demand fast and decisive action. In a nightmarish but plausible scenario, authoritarians may take unprecedented actions to force populations to birth, reducing parenthood to a compulsory obligation for one’s country and economy.

In the face of such a crisis, the time for intelligent political action was yesterday. However, if governments act now, choosing a humanistic and thoughtful approach, we may be able to build on the limited successes of the Czech Republic and the Nordic nations, giving us a chance in the fight against age itself.